As American society continues to grow increasingly more suburban and urban, our connection to agricultural lands and farmers is a lot more disconnected than it once was. Out of sight, out of mind, as the saying goes. The same goes for the food we eat. So long as we can go to a store or restaurant and buy it, there is no need to expend energy thinking about where it came from. If you have money, you can access calories virtually anywhere through very simple transactions. I would argue that this simplicity of accessing it, as opposed to growing or harvesting your own food, also has a disconnecting affect that makes food easy to not think about.

So, most of what we are aware of regarding farming and food today is what the marketing or the media tell us (those are both corporate-funded or owned, by the way), and as a result, we as a society tend to be misinformed or uninformed on issues surrounding food and farming. The prevalence of “greenwashing” in marketing has reached epic proportions, and the narratives that we hold around farming tend to be highly romanticized and nostalgic in nature. A great example of this is the popular Super Bowl commercial from 2013 by Dodge Ram called “So God made a farmer”. If you saw it, I bet you remember it. Lots of imagery of farmers and ranchers (and Dodge Trucks), with a voice over by the recently-deceased, and much beloved, American radio personality Paul Harvey. You can watch it here for reference. The speech was not created for the commercial, but was rather a speech he gave to Future Farmers of America back in 1978. I agree that farmers are a unique breed of people, and that this is a great commercial that really tugs on the heart strings; however, Mr. Harvey ironically forgets to tell us “the rest of the story”.

And my goal with this series is to shed some light on that story.

In simple terms, a food system connects farmers to eaters. How complex that connection is depends on the specific crop, the market that the farmer chooses to serve, and the values that each market pursues. As small farmers with a holistic world view, here at Two Bear Farm we have tried to create a food system in our community that has three components…the farmer, the environment (which includes the land as well as the community), and the consumer. Our goal as a farm is to get nutritious food from the land to the consumer while having a benefit on all three components. A win/win/win scenario, so to speak. Similarly, you may have heard of this concept in the business world as the triple bottom line of People, Planet, Profit.

And as a small farmer of vegetables, with a supportive community, we are fortunate that we have the ability to direct-market our produce to our customers via a very simple and direct system that lets us achieve this goal in a regenerative fashion. By focusing on the quality of the food we produce, we can make a decent living as farmers (yes, it’s hard work), we can take care of and even aim to improve the health of the land (including water and carbon sequestration), and we can improve the health of our customers.

But this is not the case for many farmers in our country. If you look around the Flathead Valley, most of the agricultural land you see, if it’s not sprouting storage units or houses, is producing cattle, spring wheat, winter wheat, canola, or hay. In the midwest, this would be corn, cattle, and soybeans. All of these are “commodity” crops, which are grown in large quantities to serve the global commodity market. Virtually none of this food is sold or eaten locally. Whether a farmer chooses to sell directly to local markets, or to serve the global food system is an important distinction to make, as it has had drastic effects on how farmers have fared.

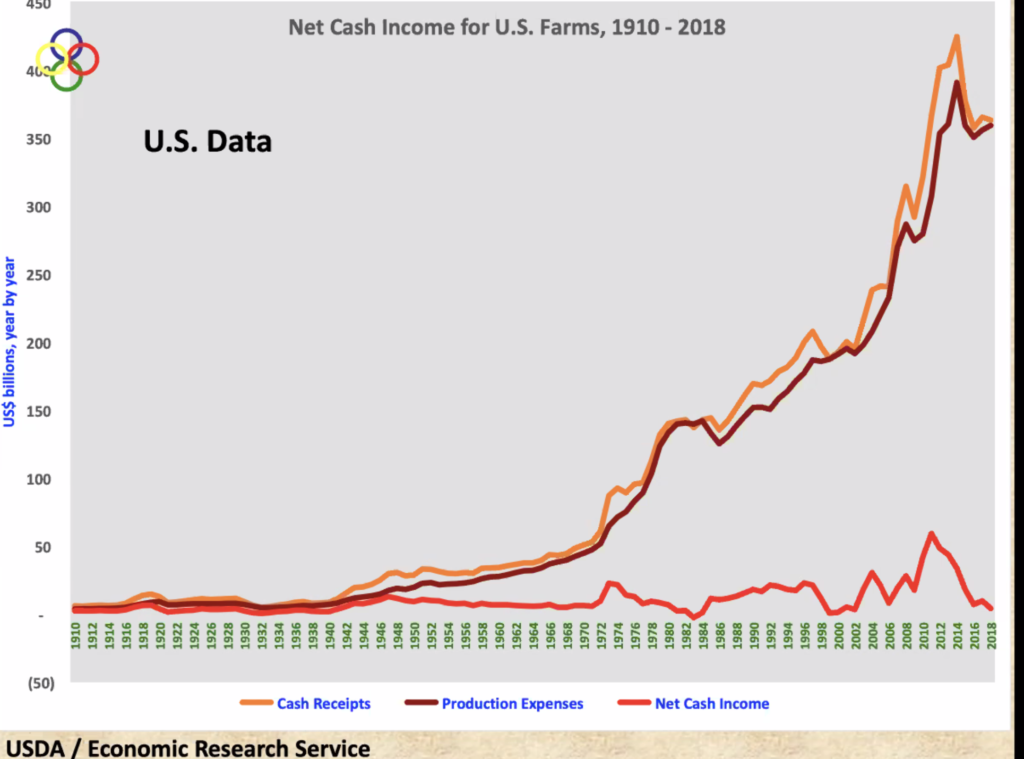

Where the local, direct-to-consumer food system has the ability to have a win-win-win regenerative relationship, the global food system tends to be a four-part system that is degenerative. There is the farmer, the landscape, the consumer, and then the corporate dominated “industry” of fertilizer producers, seed and chemical companies, Biotech firms, farm equipment and technology manufacturers, speculative investors, big banks, and the USDA. The difference between regenerative and degenerative in this case, is the addition of a Corporate Industrial sector and, more importantly, a mindset that focuses on extracting profit at the expense of all other components or values. The end result is a lose/lose/lose/win scenario, where only the industry(which does all the marketing) is doing well. Exhibit A of this relationship is a chart of USDA data that I’m borrowing from Ken Meter at Crossroads Resource Center. If hope you find this chart to be eye-opening!

Take a moment to really study this graph. This is the most concise and informative summary of American farming I have ever seen. What is it showing you? The orange line is the increase in farm production of commodity crops over the past century. It’s impressive! This increase in production is primarily a result of synthetic nitrogen fertilizers, increased efficiency of larger equipment and larger farms, plant breeding to focus on yield, and USDA policy to encourage subsidized monocrop agriculture. But these increases in technology did not come cheap, as shown by the brown line. Virtually all of the income from increased production was spent to pay for that increase in production….which means none of these advances improved the financial situation of that actual farmer, whose income is shown in red. Farm income today, with all these advances, is no higher than it was in 1920. And what is that income, you might ask? Well, the USDA reported that average farm income in 2020 was $296. Yep, you read that right…two hundred and ninety six dollars. Geez, I wonder why young kids aren’t flocking to careers in farming? To put it another way, only 8 cents out of every food dollar you spend makes it’s way back to the farmer, which is the lowest it’s ever been. So who is receiving all the money then? If you look at the gap between the red line and the brown line, that’s where the “industry” lives, and this has had major implications that I will dive into further in Part II.

I think I’ll quit there and let you chew on that for a bit. In Part II, I’m going to dig into this chart a bit more to look at how farms, and the number of farmers has changed over this same time frame. I hope you’ll join me!